An Interview with Bill Porter (Red Pine 赤松), Part 2

The Art of Translation & Book Recommendations

Hello! This is the second of a three part interview that I recently conducted with Bill Porter. Here, you’ll find our discussion about the art of translation, as well as recommendations for some of Bill’s work that I’ve enjoyed.

You can read part 1 here and part 3 here.

Before beginning, I think the topic of translation needs a little introduction! It’s not something many have stopped to think about in detail, but it’s essential to understanding East Asian spiritual practice. This is because neither Buddhism nor Daoism developed within a Western linguistic or cultural environment. Therefore, the way in which they exist in the West today is the result of translation. By seeing how translation works, we are able to understand more clearly how such traditions arrived at their present state. It also allows us to develop greater discernment regarding a teaching or teacher’s authenticity, accuracy and sources of knowledge.

Translation as Dance, Translator as Shaman

About fifteen years ago, Bill was asked to give a talk about translation, and decided that the metaphor of dance captures most accurately what he tries to do when working with a text. Here he explains it in an interview with Emergence Magazine:

“I see this beautiful woman dancing, and her dance is so entrancing that I want to dance with her, but I’m deaf. I don’t hear the music, I just see the results of her hearing the music. So, I go on the dance floor and try to dance with her. Obviously, I can’t dance on the other side of the room, nor can I put my English feet on top of her Chinese feet. This is what a lot of people think translation is. It’s literal, it’s accurate, but it kills the dance. You have to dance close enough that you pick up the energy. Especially when you’re deaf and you’re not hearing where this stuff is coming from.”

Translation requires being close enough that one’s work is accurate, but not so close that beauty and deeper meaning is stifled. According to Bill, this is one of the central skills of a translator, and it’s partly why he uses the pen name ‘Red Pine’ when translating. Red Pine was the Yellow Emperor’s rainmaker. Just as a shaman occupies a space between the human and spirit realms, so a translator must find a space between themselves and the mind of the person they are coming to translate. This is the dance.

The Practice of Translation

There are many words in Chinese that are not easily translated into English because they represent deep cultural and philosophical assumptions not found in the West. Xing (innate-nature), ming (life-destiny) and qi (see: The Cultivation of Qi) are all good examples of this. Western culture distinguishes strongly between mind and body, substance and non-substance, and it’s deeply concerned with the ‘essence’ of things. Chinese thought, on the other hand, is more inclined to view things in terms of spectrums and processes of transformation. It seems the only way to deal with this issue is via footnotes, but these can disrupt a reader and diminish the beauty one finds in reading a text.

“Ideally you don't want any footnotes. I use them all the time, but ideally you start off with the idea that you’re going to translate the text without them. Then, as soon as you begin translating you realise, gee, the reader is not going to be aware of what's behind this language. So you have to decide what crutches you need, what help you need to give your reader. Some translators fill their pages with footnotes, but if you’re actually trying to communicate the fewer footnotes the better. It's an art knowing what to include. You’ve got to use footnotes if you're going to be communicating with people who have no background in a text. You're introducing a different way of looking at things.”

Since first working on his translation of Cold Mountain’s poems in the mid-70s, Bill has published roughly 20 works of translation. This is his advice to someone just coming to it.

“When you’re just learning how to translate, you’re going to go down a lot of dead end alleys. You have to go down those alleys to find out that they’re dead ends! For example, when I first started translating Cold Mountain’s poems, I saw that each line was made up of five syllables. So, I tried writing five syllable lines in English, which is obviously impossible. Even if it wasn’t, the rhyme would still be out. You’re failures will be different to mine, but they’re thing that you are going to have to try. You have to try them to see how far they can go. It’s taken me a long time to get to the point where I can say that I know how to translate. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s going to be a good translation. It’s an art, and every artist does good work and bad work. It helps to give the project time, because you’re translations can always be better tomorrow. There’s nothing I’ve ever translated that I could not have done better if I had waited another few days or weeks. Though eventually, if you want to share your work with others, there comes a time when you have to publish. I can’t evened the books I have published because as soon as I open them I say, ‘Oh my God, I could have done better than that!’ I think the biggest thing for a translator is to get used to and accept failure. The ultimate question is always — what is in the Chinese, and is it really in the Chinese?”

We ended our discussion about translation by speaking about how Bill approaches Buddhist texts in particular.

“When it comes to Buddhist texts, the question is — where is the Dharma in this? The language that a master uses is their last ditch attempt to put something on paper that cannot be put into words. As a translator, you’re stuck with the words! You have to develop the ability to, what I call, ‘leave the words’. I think of the words as the bottom of the mountain. You start at the bottom of the mountain and you have to get to the top if you want to do something with the text and make it powerful. That’s the point — you want it to be powerful. It was a powerful text in the original. Even though it was only in words, it still had power. Words are already a failure at communication, but the more you stick with the words, the less likely you are to produce a text of value.”

Recommendations

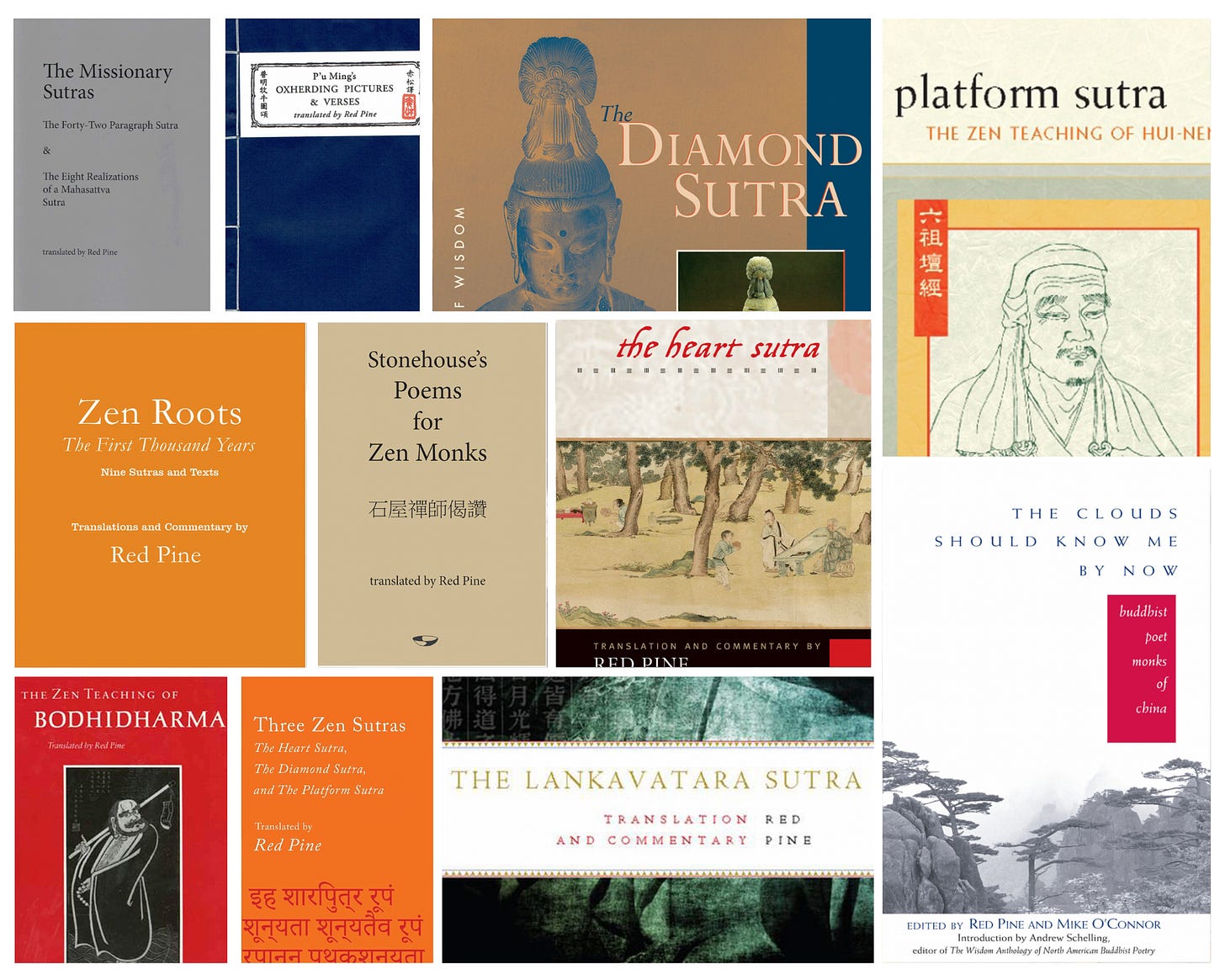

Bill’s translation work mostly covers Chan (Zen) Buddhist texts and Classical Chinese poetry. He has also combined these two genres to translate the great Buddhist poets of China’s past, such as Cold Mountain and Stonehouse. Both of them write in a direct, simple way that disguises some of the deeper meaning in the poems. Start with his The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain, before moving on to The Mountain Poems of Stonehouse.

In terms of Buddhist prose, I would begin with a new, pocket-sized edition of his translations of the Heart, Diamond and Platform Sutras. It’s called Three Zen Sutras. You can also find separate translations of each text, which come with extensive commentaries not found in the above compilation. I’d also recommend his The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma. This was the first of Bill’s books that I read, and presents four bilingual sermons said to have been given by Bodhidharma, the legendary founder of Chan (Zen) Buddhism in China. They’re very interesting if you already have some background in Chan Buddhism, but a little complicated otherwise.

It’s also worth checking out Bill’s travelogues. The most famous of these is Road To Heaven: Encounters With Chinese Hermits, which details his journeys into the Zhongnan mountains to see whether the ancient Chinese hermit tradition continued to exist. After reading this, Edward A. Burger travelled into the Zhongnan Mountains in search of a master and recorded what he found. He made it into a documentary called Amongst White Clouds, which includes stunning footage. In Zen Baggage: A Pilgrimage to China Bill visits the sites associated with the early patriarchs of Chan Buddhism, whilst in Finding Them Gone: Visiting China’s Poets of the Past he did something similar with the great poets of Chinese history. For a more straightforward piece of travel writing about China, see South of the Clouds: Travels in Southwest China.

Thank you for reading this edition of the Nüwa, and many apologies for the slight delay in publication! Part three of the interview with Bill will be released on Wednesday.

You can read part 1 here and part 3 here.

Best wishes,

Oscar

This is a wonderful explanation of the dance of translation. I first read Bil's <Road to Heaven> many years ago. I particularly loved "The ultimate question is always — what is in the Chinese, and is it really in the Chinese?”" - as so many translators of classical poetry add english words that weren't there in the original. then it becomes not a translation but a riff on the original. Which is fine, but should be upfront about what it is.

All excellent! Bill's "The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma" is a book I read again and again. Such an excellent book and I learn something new each time I read it.